Prindex Researcher Joseph Feyertag argues that corruption holds the key to unlocking tenure security.

Today, Transparency International’s latest corruption perceptions index (CPI) finds that 131 countries haven’t made progress on corruption in almost a decade.

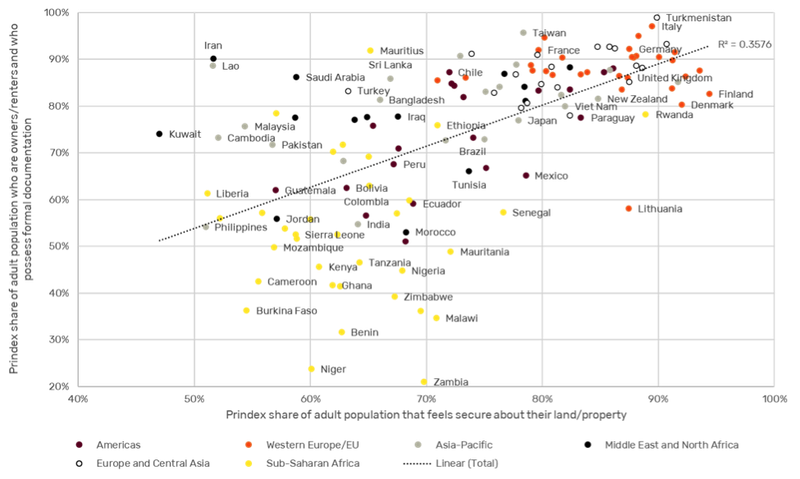

Our global survey, which last year found 1 billion people live in fear of eviction worldwide, strongly correlates with Transparency’s CPI – more so than any other development index. Citizens in top-scoring countries on the corruption index like New Zealand, Denmark and Finland also feel very secure in their land and property rights. Mirroring this, countries that score lowest on the CPI, such as Cambodia, Liberia and the Philippines, are also places where people feel the least secure (see below).

Prindex findings plotted against and Transparency International’s CPI

Source: Prindex Comparative Report 2020

This correlation suggests a close relationship between corruption and tenure security. The link is especially strong in the Americas, Western Europe and Asia-Pacific, where the spread of formal land markets – governed by title deeds and rental contracts – is most widespread. Although formalisation is seen as a panacea by many policymakers, it doesn’t always translate to higher tenure security precisely because of factors like corruption.

Corruption sows distrust in land administration, so that even people with provable legal rights can fear eviction. Our findings demonstrate this in countries like Lao and Iran where most people have documented rights to their property, but many still feel insecure. In many parts of Africa where formal rights are uncommon, ‘handing out title deeds is not enough’ to boost tenure security because trust in authorities remains low.

Formalisation doesn’t increase feelings of security in all countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (yellow dots)

Source: Prindex Comparative Report 2020

Corruption can range from fraud at the highest levels of government to petty bribery that blocks access to basic public services. Transparency International estimates that across the globe, one in five people has paid a bribe to access land services.

The end effect is to entrench the status of elites while disempowering already disadvantaged groups, such as women and young people. Communities who have cultivated their land for centuries can suddenly face unlawful eviction, cutting them off from their history, culture and identity and leaving the habitats and forests they cared for vulnerable to destruction.

Restoring trust in land governance is therefore key to delivering SDGs on land, as well as the many other areas of development that land underpins. Programmes and initiatives aimed at strengthening land rights need to be part of a wider efforts to reform and strengthen legal, policy and institutional frameworks related to land.

A first step is making land governance more transparent, efficient and participatory at all levels. This can involve new technologies, such as tablets, low-cost GPS and drones, which can increase transparency and ensure high levels of bottom-up social participation.

Transparency International’s Topic Guide on Land Corruption presents several other ways to tackle land corruption, including better institutional oversight and gender-sensitive approaches. While land rights issues such as social exclusion, economic inequality and climate change must remain a priority, tackling corruption could hold the key to unlocking tenure security and a host of other development wins.

Photo by futureatlas.com via Flickr